Take Me to Snurch: Bringers of Divine Serpent Wisdom and Inspiration

- Renée Whitehouse

- Jun 7, 2022

- 15 min read

Why did it have to be flying snakes? Because they are fascinating. What are the archaeozoological implications of a flying snake? Does it have wings? Does it have legs? Well, sometimes.

Is it an animal or more specifically human? Or a bit of both? Again, one will often find that it depends on the individual myth, even more specifically than the culture and time period.

The difference between the looks that various cultures give to serpents. It's a bit of a modern 'f*** you' toward the rest of the world that there is such animosity pointed toward snakes that stems from the Christian mythology/religion. This, if even subconsciously, continues to influence the perception of snakes. But there are so many more examples of strength and wisdom. And sure snakes are dangerous, they can hurt us, but just like broad bouncers at clubs that also makes them ideal protectors.

To be clear, these are not dragons, I'm not discussing Yuan-ti or Nāga or all individual names for the lower body of a snake, or upper body of human individuals from various mythologies. Neither am I talking about the world serpents, cyclical tail biting serpents, mythical serpent monsters, nor even just mythical snake snakes. I've decided to narrow my focus to snakes with feathers or plumage, which includes snakes with wings. While there are many examples representing the formers, from all over the world, I tried to investigate how universal the plumed/feathered serpent idea has been. And, well, it really hasn't.

Couatl

The Couatl, a medium-sized lawful good celestial, are divine caretakers said to be guardians created by a benevolent god at the beginning of time (D&D Monster Manual: 269). This being, along with the majority of Dungeons and Dragons gods and monsters, were and continue to be inspired by the characters of the ancient world.

Starting with the modern take on a snake-like creature may be the first step for many people into mythological figures. While this can be detrimental due to a skewed image of how this being was supposed to be (Tiamat is a good example of this) whoever the writer is for this divine being got a decent amount in line with the general consensus of how this deity would act. Of course, in mythology, there is typically only one, not a species, and typically on the stone working and paintings depicting one of the gods of creation, they aren't shown with wings, just feathers. In the image above, from the monster manual, you can see how awesome it looks and artistic license is completely beneficial. Obviously, I can't and won't speak for the artist, so I just wonder if they also pulled inspiration to add the wings based on the cobra goddess Wadjet when combined with the vulture goddess Nekhbet, the snake with bird wings. Either way, I'm completely pro this Dungeons and Dragons deity-creature that shows these unordinary chimaera creatures in a positive light.

Examples from the Olmeca - Juxtlahuaca cave and La Venta Stelae 19

Now, retracing the myth back to what is understood by historians to be the first example of this god, at least in the Americas is from the Olmeca. Some of the earliest representations of feathered serpents in Mesoamerica appear in the Olmec culture [c. 1500–400 BCE] (Coe, 1968; Diehl, 2004). During the formative period, in caves in the state of Guerrero, Mexican murals linked to the Olmec motifs and iconography were painted (Grove, 2000). This wide-sweeping cultural touchstone extended from the Gulf of Mexico to Nicaragua, likely thanks in part to the expansive trade routes built on high-value materials such as 'greenstone', shell, and obsidian (Hirth et al, 2013). Most surviving representations in Olmec art, such as the painting in the Juxtlahuaca cave (see below), show the Feathered Serpent as a crested rattlesnake, sometimes with feathers covering the head, the body, and sometimes including legs, and often in close proximity to humans like in Monument 19 at La Venta, c. 1200/1000-400 BCE (Diehl, 2004; Garcia, 2011) [see below]. It is believed that entities such as the feathered serpent were the forerunners of many later Mesoamerican deities because the Olmec culture predates the Maya and the Aztec (Covarrubias, 1957: 62; Joralemon, 1996: 58) although experts do disagree on the feathered serpent's religious importance to the Olmec due to the lack of lasting documentation like the Popul Vuh, which records the Maya culture (Diehl, 2004: 103–104). H.B. Nicholson notes that as early as the Middle Formative (Preclassic) in the Olmec tradition, images of serpents with avian characteristics were often represented in several types of artefacts and monuments (Nicholson, 2001). This composite creature (a chimaera) has also been called the “Avian Serpent” and “Olmec God VII,” and appears to constitute an earlier form of the later full-fledged Feathered Serpent, the rattlesnake covered with feathers, perhaps with at least some of the same celestial and fertility connotations as in later documented myths (Garcia, 2011; Nicholson, 2001).

A Feathered Serpent from deep in the Juxtlahuaca cave, the red Feathered Serpent has a crest of faded green feathers. Photo courtesy of Matt Lachniet, the University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

La Venta Stelae 19 (c. 1200/1000-400 BCE), depiction of Avian Serpent God from the La Venta site in the Olmec Heartland. Photo courtesy George & Audrey DeLange.

Feathered serpent - Teotihuacán

An overlapping and slightly later dating site in South Central Mexico is the gridded city site of Teotihuacán c. 200 BCE-700 CE also features a feathered serpent, shown most prominently on the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, built c. 150-200 CE (Castro, 1993; Taube, 1992; 1995) [see photos below]. On the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the Serpent itself is the prominent form, with the body appearing to be swimming among the shells and on its tail, just before the rattle is wearing masks which have been suggested to represent either: Tlaloc, the human and snake-like god of rain, a "war serpent" as claimed by Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube (Miller & Taube,1993:162), or that the mask represents the "fire serpent" wearing a headdress with the Teotihuacán symbol for war, Michael D. Coe claims (Coe, 2002). It is also thought, by some, that in the eyes of these figures there is a spot for obsidian glass to be put in. This can further connect these serpent depictions to the Olmec culture and trade and their version of the god itself.

All photos in this group are courtesy of me, taken at Teotihuacan in the summer of 2014.

*Teotihuacan Research Laboratory: https://teo.asu.edu/about/about

K’uk’ulkan [God H] - Maya

In the region from Chichen Itza down to Guatemalan highlands the Feathered Serpent God got a name. In Yucatec Maya tradition the name is K'uk'ulkan, in K'iche' Maya, Q'uq'umatz. No matter the spelling, these different names are believed to be representing the same Flying Serpent God and all as part of the same multi-region cult (Braswell, 2013L; Recinos et al., 1954). According to Miller and Taube (1993), K'uk'ulkan was rare in the Classic Maya Civilization, but in the K'iche' Popol Vuh, Q'uq'umatz, the God associated with water, clouds, the wind and the sky, teamed up with Tepeu, God of lightning and fire, who were the duo of Gods that created humanity (Carmack, 2001; Christenson 2003, 2007; McCallister, 2008). While Qʼuqʼumatz may originally have been the same god as Tohil, the Kʼicheʼ sun god who also had attributes of the feathered serpent, they seemed to later have diverged (Fox, 1987; 2008). This also played a role in the ballgame myth with the hero twins and thus has shown up on ballcourts as markers [photo below] (Fox, 1987; 2008). Qʼuqʼumatz's main job is to carry the sun across the sky and down into the underworld and thus acted as a mediator between the various powers in the Maya cosmos (Fox, 1987; 2008; 1991).

A few examples of this diety are also found in Yaxchilan as the "Vision Serpent", shown as detail on Lintel 15 [photo below] and is depicted on pillars. Another example is when the flying serpent is sitting atop the World tree in Palenque as I've discussed in my old Pakal Coffin Lid post. War Serpent or Waxaklahun Ubah Kan was another one of the names for the Classic period version of K'uk'ulkan which extended past the Classic period into the Post-classic and out of the initial Maya area. One of the examples from after the main part of the Classic Period from Labna, a palace site built in the Late and Terminal Classic periods that have "serpents adorn[ing] the corners of the principal facade. Characteristic of the Vision Serpent, there appears to be either an anthropomorphic deity or the spirit of an ancestor emanating from the gaping jaws of the serpent's mouth" (Ivanoff, 1973). And in the post-classic period, the God's following was found all the way to the Guatemalan Highlands (Sharer & Traxler, 2006).

On one of the buildings of Uxmal (Yucatec Maya: Óoxmáal) in the nunnery quadrangle, a flying serpent is built into the lattice design [photos below]. From the Terminal and Post-Classic on, the balance of powers shifted over time and the ruling powers moved north and built Mayapán (Màayapáan in Modern Maya) and Chichen Itza, two more examples of sites in the Late Postclassic that were both built in the state of Yucatán, Mexico [pictures below].

1) Ballcourt marker at Mixco Viejo, depicting Qʼuqʼumatz carrying Tohil (as the sun) across the sky in his jaws. By Simon Burchell, 2005.

2) A Vision Serpent, detail of Lintel 15 at the Classical Maya site of Yaxchilan.

3) Snake and traditional Mayan lattice. Leon Petrosyan, 2018.

4) Uxmal, at the night show. My own photo, 2013.

5 & 6) Serpent motif at the beginning of one of the pyramids at Mayapán. My own photos, 2013.

7) Kukulkan at the base of the west face of the northern stairway of El Castillo, Chichen Itza. Photo by Frank Kovalchek in 2009.

Queztalcoat'l

The name, in parts, means quetzalli - "beautiful" like the quetzal bird and coat'l - "snake or serpent". He was also a human king man, and like in the Mayan tradition, he was the God of the wind and sky and was part of the quartet of Gods who created the different versions of the world and brought humanity to what it is now in the time of the 5th sun (Aguilar-Moreno, 2006; Smith, 2003). He stood for or was related to gods of the wind, of the planet Venus, and of the dawn, as well as a patron god of merchants and of arts, crafts, learning, and knowledge (Smith, 2003).

1) Quetzalcoatl in human form, using the symbols of Ehecatl, from the Codex Borgia.

2) Quetzalcoatl in feathered-serpent form as depicted in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century.

Wdjt

The cobra goddess of ancient Egypt, Wadjet or Wadjit, Wedjet, Uadjet or Ua Zit, and wꜢḏyt which means "Green One" in Ancient Egyptian (Budge, 1969). has many spellings because of changes in pronunciation over time and location, and many vowels weren't recorded in hieroglyphic texts. In Greece, she was also called Buto, Uto, or Edjo and because of similarities between myths was likely compared with this myth to the Greek story of Leto and Apollo on Delos ("Wadjet|Egyptian goddess" Encyclopedia Britannica). In early periods, before unification, she was a patron goddess of the city of Dep and while she was also a city goddess in Upper Egypt she was the major goddess of all of Lower Egypt before unification (Wilksinson, 2002; 2003). While she's sometimes depicted as a snake-headed woman she is often shown as just a snake [photos shown below]. Wadjet was the rearing cobra shown on the crown of the pharaohs.

Upon unification, she became the joint protector of the Pharoah and of all of Egypt along with Nekhbet. Wadjet had a large temple at the ancient Imet (now Tell Nebesha) in the Nile Delta. She was worshipped in the area as the "Lady of Imet" and later she was joined by Min and Horus to form a triad of deities (Razanajao, 2006). Other than being the protector and guardian of kings she was also a protector of women in childbirth because in some myths Wadjet was said to be the nurse of the infant god Horus. With the help of his mother Isis, they protected Horus from his evil uncle, Set, while they took refuge in the swamps of the Nile Delta ("Wadjet|Egyptian goddess" Encyclopedia Britannica). She was also an extremely powerful goddess whose gaze was said to slaughter enemies.

Wadjet and Nekhbet, the vulture-goddess of Upper Egypt, were the protective goddesses of the king and were sometimes represented together on the king’s diadem, symbolizing his reign over all of Egypt. The form of the rearing cobra on a crown is termed the uraeus which was the emblem on the crown of the rulers of Lower Egypt. Nekhbet, also spelt Nekhebit, the vulture, is an early predynastic local goddess in Egyptian mythology, who was the patron of the city of Nekheb (her name means of Nekheb). Ultimately, she became the patron of Upper Egypt and one of the two patron deities for all of Ancient Egypt when it was unified (Wilkinson, 2003).

Uraeus with the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. Late Period of Egypt, 664–332 BC.

Egyptian goddess Wadjet (painting from the tomb of Nefertari, ca 1270 BC)

Wadjet

A gold amulet of Wadjet (from Tutankhamun's tomb, ca 1320 BC)

Nekhbet with staff and shen ring and the crown of Upper Egypt.

Mask of Tutankhamun's mummy featuring a uraeus, from the 18th Dynasty. The cobra image of Wadjet with the vulture image of Nekhbet represents the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt.

Four golden uraei cobra figures, bearing sun disks on their heads, on the reverse side of the throne of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1346–1337 BC). Valley of the Kings, Thebes, New Kingdom (18th Dynasty).

Papyrus Udjat (wadjeti) Eye Of Horus Protective Amulet Wadjet Serpent Goddess and Nekhbet

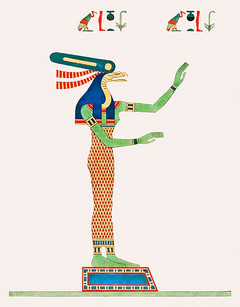

1) Wadjet illustration from Pantheon Egyptien (1823-1825) by Leon Jean Joseph Dubois (1780-1846).

2) Renenutet sitting on a throne holding a papyrus staff. By Rowanwindwhistler, 2010.

3) Meretseger, an ancient Egyptian cobra headed goddess. Based on New Kingdom tomb paintings.

4) Two images of Wadjet appear on this carved wall in the Hatshepsut Temple at Luxor. From Steve F.E. Cameron, 2006.

5) Black granite statue of Meretsger protecting Pharaoh Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BC). From Karnak, in Cairo, Egyptian Museum, main floor, room 12.

In the above gallery, I also included images of goddesses with different names and various domains, but are tied together through the complications of history.

Renenutet

She is depicted as a cobra or as a woman with the head of a cobra. As a general snake with the feather of Ma'at on her head, she is the goddess of nourishment and the harvest, so many offerings were presented to Renenutet during the annual harvest time (Pinch, 2004). The verbs 'to fondle, to nurse, or rear' can explain the name Renenutet because this goddess was a 'nurse' who took care of the pharaoh from birth to death (Flusser & Amorai-Stark, 1993). She was also the female counterpart of Shai, "destiny", who represented the positive destiny of the child. In Greece, she was the Thermouthis or Hermouthis and embodied the fertility of the fields and was the protector of the royal office and power (Dunand & Zivie-Coche, 2004).

Sometimes, as the goddess of fertility and nourishment, Renenutet and her sometimes husband, Sobek, the crocodile-headed god representing the Nile River, worked together for the annual flooding which deposited the fertile silt that enabled abundant harvests. The temple of Medinet Madi, a small and decorated building in the Faiyum, is dedicated to both Sobek and Renenutet (Dunand & Zivie-Coche, 2004). When Renenutet's husband was Geb she was said to be the mother of Nehebkau, who was occasionally also represented as a snake, who represented the Earth. In later dynastic periods, she was a snake goddess that was worshipped over the whole of Lower Egypt. Over time Renenutet was increasingly associated with Wadjet and eventually, was even identified as an alternate form of Wadjet herself.

Meretseger

Meretseger was the patron of the artisans and workers of the village of Deir el-Medina, who built and decorated the great royal and noble tombs (Spencer, 2007). Desecrations of rich royal burials had already been happening since the Old Kingdom of Egypt (27th/22nd century BC), and sometimes, even often by the workers themselves. Therefore, the genesis of Meretseger was to fulfil the need to identify a guardian goddess, as both dangerous and merciful of the elite, as are most goddesses (Hart, 1986). Meretseger was sometimes portrayed as a cobra-headed woman, though this iconography is rather rare ("Gods of Ancient Egypt: Meretseger". www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk) and in this case, she could hold the was-sceptre as well as having her head surmounted by the feather of Ma'at and armed with two knives ("Stela Showing Meretseger, Ancient Egypt collection". www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk; Peacock, Lenka. "Goddess Meretseger at Deir el-Medina". www.deirelmedina.com). More commonly, she was depicted as a woman-headed snake or scorpion,(Peacock, Lenka. "Goddess Meretseger at Deir el-Medina". www.deirelmedina.com; "MERT SEGER in "Enciclopedia dell' Arte Antica" ". www.treccani.it) or sometimes a cobra-headed sphinx, lion-headed cobra or a three-headed [woman, snake, and vulture] cobra ("Gods of Ancient Egypt: Meretseger". www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk). On various steles, she wears a modius surmounted by the solar disk and by two feathers, or the hathoric crown [the solar disk when between two bovine horns - photo #5 above] (Peacock).

Soft Conclusions

Some Meanings

These can also sometimes go for other mythical snakes and snake-like creatures in general.

wisdom

fertility - The importance of the Earth to remain fertile.

protector

guidance

a bridge between our world and the afterlife (Ra's journey each night - more just snakes)

What I previously discussed are a few examples of the magical flying serpent deities from ancient mythologies up to modern-day folklore, and pop. culture. This is by no means a comprehensive study and is only based on my own limited experience and research into the aspects of the inspiration behind the tattoo I finally got after almost a decade of planning. There are so many other examples of wisdom bringing serpents from around the world. Some have been/are directly connected to or are venerated for the act of bequeathing knowledge or wisdom to humans and are seen as having either an ultimately 'good' or 'evil' motivation. Some are deities or representatives of those deities who rule over those particular aspects. But, for whatever flexible reason, as cultures reach even similar ideas from completely different starting points, serpents seem to have a valuable place in human culture. And, in the disconnected majority, as guardians, protectors, providers of wisdom, and connections between our world and a world beyond.

Wisdom is constantly changing growth by looking outside oneself and asking, how can I improve. It's an ongoing battle between multiple worlds of competing advice that can only be answered by understanding and a realization that there is more to learn. Listening to and discussing topics and being open to change and different ideas and values (that do not need to be followed) can lead to new ideas and adventures never had. In spiritual contexts, we can acknowledge a belief that this balance is a gift between our lives here on Earth and some divine imagination of the heavens, a gift from any specific deity who saw humans as having great potential**. Wisdom is working with cognisant thoughts, which can give us hope or anxiety on any given day, letting us reason that just because a tomato is a fruit doesn't mean it [necessarily] belongs in a smoothie (even though vegetables are regularly added and taste delicious). As these two worlds are brought together through reasoning out the world around us with wisdom it's logical that most, if not all, cultures create such deities to be connected to the heavens and Earth, and be willing and even wanting to share their wisdom with others.

These are the ideals that I want to remind myself of every day. So I permanently put it on my arm. There are so many more deities and representations that take on a serpent form, which I'll discuss in a later post. This post was about those that instilled me with inspiration.

Bibliography

Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel (2006). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Los Angeles: California State University.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2011, November 2). Wadjet. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Wadjet.

Budge, E. A. Wallis (1969). The Gods of The Egyptians. or Studies in Egyptian Mythology, 2.

Castro, Ruben Cabrera (1993) "Human Sacrifice at the Temple of the Feathered Serpent: Recent Discoveries at Teotihuacan" Kathleen Berrin, Esther Pasztory, eds., Teotihuacan, Art from the City of the Gods, Thames and Hudson, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Coe, Michael D. (1968) America's First Civilization, American Heritage Publishing, New York.

Coe, Michael D. (2002); Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs London: Thames and Hudson.

Coe, Michael D. (2005); "Image of an Olmec ruler at Juxtlahuaca, Mexico", Antiquity Vol 79 No 305, September 2005.

Covarrubias, Miguel (1957). Indian Art of Mexico and Central America (Color plates and line drawings by the author ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 171974.

Diehl, Richard A. (2004) The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Thames & Hudson, London

Dunand, F., & Zivie-Coche, C. (2004). Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Cornell University Press.

Flusser, D., & Amorai-Stark, S. (1993). The Goddess Thermuthis, Moses, and Artapanus. Jewish Studies Quarterly, 1(3), 217-233.

Fox, John W. (2008) [1987]. Maya Postclassic state formation. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Fox, John W. (1991). "The Lords of Light Versus the Lords of Dark: The Postclassic Highland Maya Ballgame". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 213–238.

Garcia, S. A. (2011). Early representations of Mesoamerica’s feathered serpent: Power, identity, and the spread of a cult (Master’s thesis). Ann Arbor: ProQuest.

Grove, David C. (2000) "Caves of Guerrero (Guerrero, Mexico)", in Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: an Encyclopedia, ed. Evans, Susan; Routledge.

Hart, G. (1986). A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses.

Hirth, K., Cyphers, A., Cobean, R., De León, J., & Glascock, M. D. (2013). Early Olmec obsidian trade and economic organization at San Lorenzo. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(6), 2784-2798.

Ivanoff, Pierre (1973). Monuments of Civilization: Maya. New York: Brosset & Dunlap.

Joralemon, Peter David (1996). "In Search of the Olmec Cosmos: Reconstructing the World View of Mexico's First Civilization", in Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, eds. E. P. Benson and B. de la Fuente, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., ISBN 0-89468-250-4, pp. 51–60.

Miller, M. E., & Taube, K. A. (1993). The gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya: an illustrated dictionary of Mesoamerican religion. Thames & Hudson.

Nicholson, H. B. (2001). "Feathered Serpent." In David Carrasco (ed).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press.

Peacock, Lenka. "Goddess Meretseger at Deir el-Medina". www.deirelmedina.com.

Pinch, G. (2004). Egyptian mythology: A guide to the gods, goddesses, and traditions of ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, USA.

Razanajao, V. (2006). D'Imet à Tell Farâoun: recherches sur la géographie, les cultes et l'histoire d'une localité de Basse-Égypte orientale (Doctoral dissertation, Montpellier 3).

Recinos, Adrian; Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (1954). "Popul Vuh, the Book of the People". Los Angeles, USA: Plantin Press.

Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Spencer, A. J. (Ed.). (2007). The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. British Museum.

Taube, K. A. (1992). The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred war at Teotihuacan. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 21(1), 53-87.

Taube, K. A. (1995). The rainmakers: the Olmec and their contribution to Mesoamerican belief and ritual. The Olmec World: ritual and rulership, 83-103.

Wilkinson, T. A. (2002). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 213–214

Richard, H. W. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.

------------------

**Stargate SG-1 throwback

Comments